Incredible results within some clinical trials are showing up for cancer treatments where genetically modify patients’ blood cells are created to target specific cancer disease.

Based on two clinical trials, nearly 90% of patients had their leukemia disappear after receiving an experimental therapy using genetically modified CAR T-cells. These trials were sponsored sponsored by Novartis AG NOVN.VX -0.72% of Switzerland and Seattle-based biotech Juno Therapeutics Inc. The results were published in December and February of 2014.

Both trials included just a few patients: 22 children in the Novartis trial and 16 adults in the Juno trial. All patients had a common childhood cancer, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and these patients each had exhausted standard cancer treatments.

According to Dr. Daniel DeAngelo: “CAR T-cells are probably one of the most exciting concepts and fields to come out in cancer in a very, very long time.” Dr. DeAngelo is a Boston-based hematologist and associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. He was is not involved in either of the clinical trials.

In an interview with The Wall Street Journal, Dr. Usman Azam said “I think that a cure for cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma through a CAR technology is plausible. Oour job is to get this into patients as soon as we feasibly can.”

Dr. Azam is the leader of cell and gene therapies at Novartis, and also heads the new unit Novartis created partly to speed the therapies’ time to market.

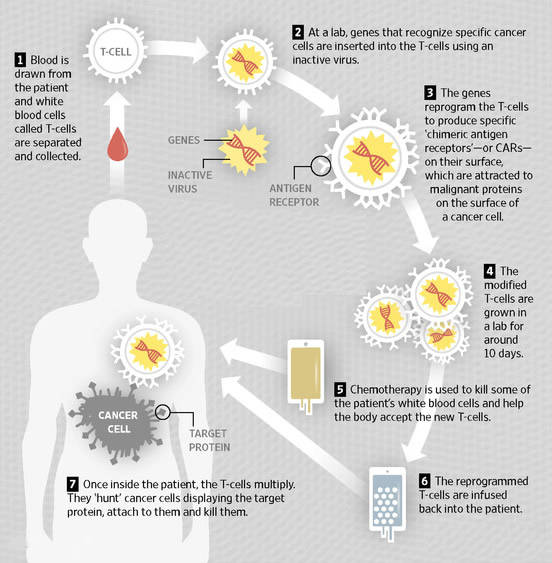

T-Cell CAR therapies combine the methods of genetic tweaking and “immunotherapy,” which uses the patient’s immune system to fight disease. The genetic part of the method involves extracting disease-fighting white blood cells called T-cells from a patient’s blood. The T-cells are then genetically modified, grown in a laboratory dish for around a short period of time, and then injected back into the patient.

The laboratory dish process is where T-cells are combined with a disabled virus. The virus enables the T-cells to produce Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CARs) that can recognize and target malignant proteins on the surface of cancer cells.

Novartis is funding the development of their treatment in partnership with the University of Pennsylvania, while Juno’s funding is in partnership with teams at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, Seattle Children’s Hospital and Seattle’s Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

For patients seeking potential solutions to their cancer, knowing who is developing new treatments brings them to the opportunity to participate in Clinical Trials to get early results to cancer cure. Therefore, while Novartis and Juno are ahead in the race to bring Genetically Modified T-Cell cancer therapy to the mass of cancer patients, there is also others developing similar therapy methods including Pfizer Inc., PFE -0.04% Kite Pharma Inc. KITE -3.75% and Celgene Corp. CELG -1.14% (in collaboration with Bluebird Bio Inc. BLUE +1.43% ).

Genetically modified T-Cell therapy deploying CARs is very new; so there are unresolved questions about the method of using this kind of therapy.

How Long Does T-Cell CAR Treatments Last Keeping Cancer In Remission?

Because the current clinical trials treated only a small number of patients, as well as many of those patients whose cancer went into remission after the T-Cell CAR treatment where then eligible for subsequent stem-cell transplants (which can also increase survival), there is no absolute evidence and history to yet determine the longevity this treatment produces.

Additionally, there is a potential dangerous side effect for some patients called “cytokine-release syndrome,” an immune response while the therapy is working, can cause a sharp drop in blood pressure and surge in the patient’s heart rate.

In March 2014, a Juno-backed Sloan-Kettering trial was held over the deaths of two patients. That has caused a temporary halt in the T-Cell CAR study because of worries about the dangerous immune response and two deaths.

But, the clinical trial is again recruiting patients giving those with very advanced leukemia fewer modified cells, and excluding those patients with a risk of heart failure.

Can T-Cell CAR Treatments Be Created At Affordable Cost?

Due to the genetic engineering involved with T-Cell CAR therapy which is very complex to manufacture with each laboratory batch being a unique personalized treatment customized to a cancer patient’s own blood cells, the inability to mass-produce T-Cell CAR therapy questions the implication about how much companies will charge for the therapy.

Dr. Malcolm Brenner, director of the Center for Cell and Gene Therapy at the Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston, reminds us that “What we’re talking about here is a single, very expensive therapy that’s used once for a specific patient and is not generalizable.”

While Citigroup believes T-Cell CAR therapy could cost in excess of $500,000 per patient, which it notes is roughly the same cost for a stem cell transplant, most analysts still think it is too soon to approximate the future revenue or price for this therapy.

Again, Dr. DeAngelo clarifies: “This technology needs to be widely developed and accessible to patients; if the cost is going to be a hindrance, it’s going to be a really sad day.”

For these reasons and more, Pfizer is taking a different approach to this treatment with a focus on managing scalability and cost. “We would like to take it to the next level, where CAR therapies become a more standardized, highly controlled treatment,” said Mikael Dolsten, Pfizer’s head of global research and development.

Pfizer wants to develop a generic T-Cell CAR therapy for use in any patient, potentially lowering its cost. So, Pfizer is collaborating with French biotech Cellectis SA, ALCLS.FR +1.89% on T-Cell CAR research that is currently preclinical.

Even if T-Cell CAR treatments being developed might justify “outrageous” prices, it is probably that health-care payers as well as patients might object and fight back. International director of health-care research at Société Générale, Stephen McGarry, asks: “When you look at the initial data with the Novartis therapy, you’re getting cures in some kids—what do you charge for that?”

So, the drug companies and biotechs must overcome big hurdles to get their T-Cell CAR therapies into hospitals, and manage their potential cost. And the biggest challenge may be the cost of the therapies.